« Dépasser les Pèlerins »

2013

Text published in the exhibition catalogue of Raymonde April: La Maison où j'ai grandi, presented at the Musée du Bas-St-Laurent, Rivière-du-Loup, Québec. (English translation)

Raymonde April, Albums, 2005, détail

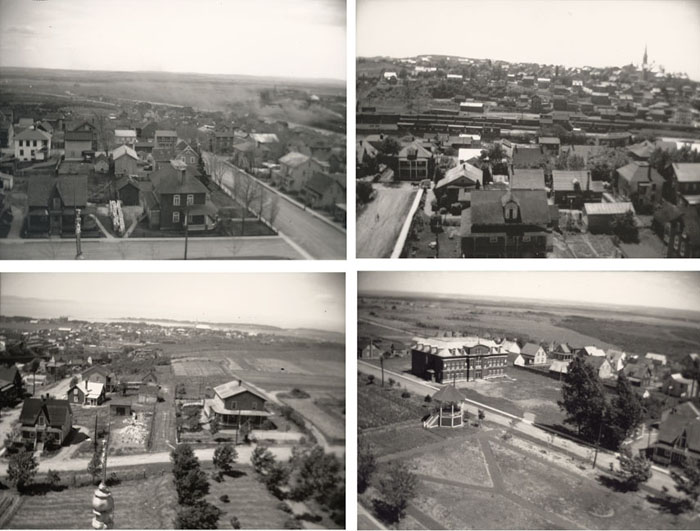

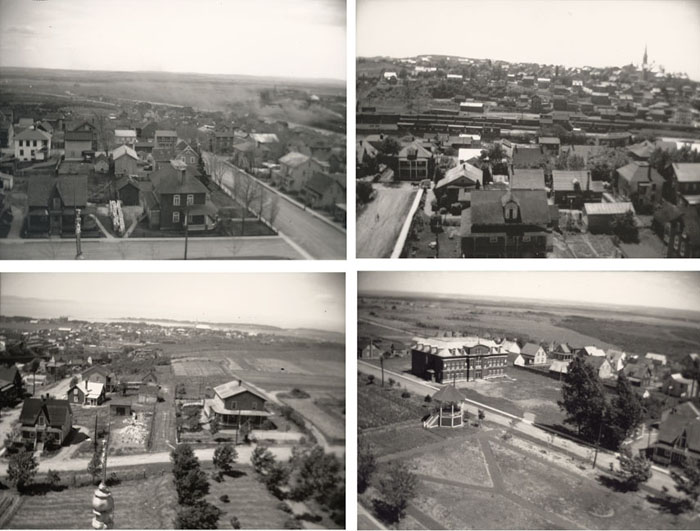

From a high plateau of Rivière-du-Loup, the eye is drawn to the vertiginous course of the river as it descends to the St. Lawrence in a series of cascades, and the city takes on the appearance of an ancient stone staircase connecting the land to the river. In the panorama, churches stand out as landmarks, piercing the sky with their silvery steeples, and at the top of St. Ludger Church, a rare point of view allows one to survey all directions, as from a look-out tower. To the east is the old Collège; to the west, trains rest on the tracks and the city’s largest church keeps watch, still dominating from the top of its hill. To the north is the long stretch of the river, and, finally, far to the south, the open countryside. Closer to us, at the corner of the street, is the house Raymonde April grew up in.1

The house, which is no longer her house, is in a neighbourhood bordered by the Rivière du Loup. She crossed the threshold a long time ago and followed the length of the river to Quebec City, and, later, to Montreal. When she returns to pay it a visit from time to time, mostly during the summer, she walks around the house like a stranger, reacquainting herself with familiar motifs: the pillars and the balustrade, the unrepairable crack in the foundation, the tree whose growth she measures, the view of the house across the street. Everything is there, but today her house is nothing but a Proustian memory, like that of the protagonist of Remembrance of Things Past who recalled the places of his childhood, “as though all Combray had only consisted of but two floors joined by a slender staircase, and as though there had been no time there but seven o’clock at night.”2 All that remains of this memory is an inventory of circumscribed, atemporal, and inalterable details. It will always be there, this crack in this corner of the house, despite all attempts to seal it.

Without straying too far, the artist begins to wander, to descend the plateaus by haphazard routes, without a destination, as though on an improbable pilgrimage. She listens discreetly to the latest rumours: the news of a marriage, a birth, or a death, interspersed with comments about the visit of a famous actress or a celebration to take place on Rue Lafontaine. She hears them but lets them drift into the wind, turning to her own rumours. Taking possession of what she sees, she collects images everywhere, and everywhere impressions of déjà vu. She photographs them again and takes them home with her.

Placed side by side, the photographs form a partial topography of the city: an old wooden house faces the railway bridge that spans the river down which the turbulent water from the spring thaw rushes to the falls, depositing a misty filter of fine droplets on the high rock face as it surges by –motionless scenes in which people never appear except by chance. While “time passes, the memory holds fast,” wrote Françoise Sagan.3 Always in the same place, at the same time of day, there is the mirage of this girl’s distant gaze, men standing around talking next to their cars, teenagers and their bicycles, seen from the elevated position of the front steps of her former house. In this way, time has passed and memory has held fast. These images are like so many gazes towards the center of the city–as into a box that contains a whole world, one in which the sun never sets on spring afternoons.

A little like her house, Raymonde April’s life is something we rarely see inside of. We share her view of the outside, the gaze she projects on other people, on landscapes. Once the photographs break away from this, they shift about like ghosts with no house to haunt. They appear then disappear, until we forget them and they surprise us by showing up again in places where we don’t expect them. Even if we don’t often see her, the artist is never very far away; when we do catch a glimpse of her, she is often blurred, or drawing herself in the familiar lines of certain faces, or in the eyes of those around her. Sometimes, we imagine that we have found her in a particular place, and it is as though we could locate her on a map. But she may already be far away, in the big city, in a new novel, in a Nouvelle Vague film, or in a Françoise Hardy song. Or perhaps she’s already back in Rivière-du-Loup, drawing up new stories.

The set is in place, the scenes are ready to be shot. The extras will soon arrive, coming from far away to find a place in her photographs, to enter her world and open up its horizons. She’ll amble along the country roads with them, get lost for a while, before rediscovering the path leading to the river, to their rallying point on the shore. Once everyone has arrived, they’ll catch their breath, and then walk serenely along the shifting edge, where the land joins the sea and the tides enlarge or diminish the city a little. Following the striated rocks, they’ll skim along the water’s edge until they can’t go any farther without getting their feet wet. Time will pass so quickly that the water will rise up to their knees, and so they will return to the riverbank, watch the sunsets together, listen to the peaceful sound of the wind in the trees, pick little fruits, and turn the landscape inside-out, scattering it with impromptu kisses, with music never to be played again. On the dreaded day, her extras will go their separate ways, their pockets filled with pebbles.

The view of the river is the limit of her lived space and the beginning of the observed, imagined landscape. In the evening, gazing at the unknowable lights on the distant shore on the other side of the river, she told herself that “the lights over there were the same as here and came from a beacon, a house, a fire, an airplane, a pole, or a car. I loved them from afar.”4 Two cities as in a mirror, their stories mingling in their reflections. On moonless nights, nothing remains except the lights, and, in the space between them, the song of the seals. “There is therefore nothing left to do but listen, as intensely as possible, to these strange songs, until high tide, until the storm, until autumn, until my departure.”5 The summer has gone by as quickly as a day in late August.

As to remind us of imminent departures, five small islands, the Pèlerins, lie on the St. Lawrence close to Rivière-du-Loup. When we leave the city heading west, they calmly accompany us on our right; once we’ve passed them, the city and the summer are already far behind. Her “heart silenced by an ungraspable lament, still and snowy,” the young Raymonde April meditated on her destination: “Leaving to study, to work, to make a life, to settle in the big city, to love and suffer there, to start projects, to keep appointments, to pick up the pieces, to fly to other countries.”6 Since then, each time her photographs passed beyond the Pèlerins, the work has meant something different. The images also migrated to the big city, to settle there, do their work there, make a life for themselves, take a plane to other countries. They have been the raw material for so many stories that one has lost sight of where they came from. However, a thin thread hangs on, and it is still possible to make one’s way back to the source. If April regularly returns to Rivière-du-Loup, her work returns less often.When it does pass through, we take hold of it and embrace it.

1 Raymonde April found old photographs of these four views among her family souvenirs, and commented on them in Album XI of Aires de migrations (2005): “To the south: the house, the fields. To the west: the trains and St. François-Xavier Church. To the north: the River. To the east: the Collège and the park.”

2 Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, Volume One : Swann’s way, trans. C. Scott Moncrieff (New York : Henry Holt, 1922) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/7178/7178-h/7178-h-htm (accessed 22 May, 2013).

3 Françoise Sagan, With Fondest regards, trans. Christine Donougher (New York : Dutton, 1985) p. 139.

4 Raymonde April, “A Fly in Paradise”, in Thirteen Essays on Photography, Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, 1990, p. 206.

5 Raymonde April, Soleils couchants, Québec : Éditions J'ai VU, 2004, p. 54 (freely translated).

6 It was the artist who first spoke of “passing the Pèlerins.” (“dépasser les Pèlerins”). This passage, taken from her website, differs slightly from the published version: Raymonde April, “Raymonde April,” Du souvenir au devenir: Rivière-du-Loup 2000, Cap-Saint-Ignace: Plume d'oie, 2000, p. 393.

Translation: Darcy Dunton

Editing: Craig Rodmore

2013

Text published in the exhibition catalogue of Raymonde April: La Maison où j'ai grandi, presented at the Musée du Bas-St-Laurent, Rivière-du-Loup, Québec. (English translation)

Raymonde April, Albums, 2005, détail

From a high plateau of Rivière-du-Loup, the eye is drawn to the vertiginous course of the river as it descends to the St. Lawrence in a series of cascades, and the city takes on the appearance of an ancient stone staircase connecting the land to the river. In the panorama, churches stand out as landmarks, piercing the sky with their silvery steeples, and at the top of St. Ludger Church, a rare point of view allows one to survey all directions, as from a look-out tower. To the east is the old Collège; to the west, trains rest on the tracks and the city’s largest church keeps watch, still dominating from the top of its hill. To the north is the long stretch of the river, and, finally, far to the south, the open countryside. Closer to us, at the corner of the street, is the house Raymonde April grew up in.1

The house, which is no longer her house, is in a neighbourhood bordered by the Rivière du Loup. She crossed the threshold a long time ago and followed the length of the river to Quebec City, and, later, to Montreal. When she returns to pay it a visit from time to time, mostly during the summer, she walks around the house like a stranger, reacquainting herself with familiar motifs: the pillars and the balustrade, the unrepairable crack in the foundation, the tree whose growth she measures, the view of the house across the street. Everything is there, but today her house is nothing but a Proustian memory, like that of the protagonist of Remembrance of Things Past who recalled the places of his childhood, “as though all Combray had only consisted of but two floors joined by a slender staircase, and as though there had been no time there but seven o’clock at night.”2 All that remains of this memory is an inventory of circumscribed, atemporal, and inalterable details. It will always be there, this crack in this corner of the house, despite all attempts to seal it.

Without straying too far, the artist begins to wander, to descend the plateaus by haphazard routes, without a destination, as though on an improbable pilgrimage. She listens discreetly to the latest rumours: the news of a marriage, a birth, or a death, interspersed with comments about the visit of a famous actress or a celebration to take place on Rue Lafontaine. She hears them but lets them drift into the wind, turning to her own rumours. Taking possession of what she sees, she collects images everywhere, and everywhere impressions of déjà vu. She photographs them again and takes them home with her.

Placed side by side, the photographs form a partial topography of the city: an old wooden house faces the railway bridge that spans the river down which the turbulent water from the spring thaw rushes to the falls, depositing a misty filter of fine droplets on the high rock face as it surges by –motionless scenes in which people never appear except by chance. While “time passes, the memory holds fast,” wrote Françoise Sagan.3 Always in the same place, at the same time of day, there is the mirage of this girl’s distant gaze, men standing around talking next to their cars, teenagers and their bicycles, seen from the elevated position of the front steps of her former house. In this way, time has passed and memory has held fast. These images are like so many gazes towards the center of the city–as into a box that contains a whole world, one in which the sun never sets on spring afternoons.

A little like her house, Raymonde April’s life is something we rarely see inside of. We share her view of the outside, the gaze she projects on other people, on landscapes. Once the photographs break away from this, they shift about like ghosts with no house to haunt. They appear then disappear, until we forget them and they surprise us by showing up again in places where we don’t expect them. Even if we don’t often see her, the artist is never very far away; when we do catch a glimpse of her, she is often blurred, or drawing herself in the familiar lines of certain faces, or in the eyes of those around her. Sometimes, we imagine that we have found her in a particular place, and it is as though we could locate her on a map. But she may already be far away, in the big city, in a new novel, in a Nouvelle Vague film, or in a Françoise Hardy song. Or perhaps she’s already back in Rivière-du-Loup, drawing up new stories.

The set is in place, the scenes are ready to be shot. The extras will soon arrive, coming from far away to find a place in her photographs, to enter her world and open up its horizons. She’ll amble along the country roads with them, get lost for a while, before rediscovering the path leading to the river, to their rallying point on the shore. Once everyone has arrived, they’ll catch their breath, and then walk serenely along the shifting edge, where the land joins the sea and the tides enlarge or diminish the city a little. Following the striated rocks, they’ll skim along the water’s edge until they can’t go any farther without getting their feet wet. Time will pass so quickly that the water will rise up to their knees, and so they will return to the riverbank, watch the sunsets together, listen to the peaceful sound of the wind in the trees, pick little fruits, and turn the landscape inside-out, scattering it with impromptu kisses, with music never to be played again. On the dreaded day, her extras will go their separate ways, their pockets filled with pebbles.

The view of the river is the limit of her lived space and the beginning of the observed, imagined landscape. In the evening, gazing at the unknowable lights on the distant shore on the other side of the river, she told herself that “the lights over there were the same as here and came from a beacon, a house, a fire, an airplane, a pole, or a car. I loved them from afar.”4 Two cities as in a mirror, their stories mingling in their reflections. On moonless nights, nothing remains except the lights, and, in the space between them, the song of the seals. “There is therefore nothing left to do but listen, as intensely as possible, to these strange songs, until high tide, until the storm, until autumn, until my departure.”5 The summer has gone by as quickly as a day in late August.

As to remind us of imminent departures, five small islands, the Pèlerins, lie on the St. Lawrence close to Rivière-du-Loup. When we leave the city heading west, they calmly accompany us on our right; once we’ve passed them, the city and the summer are already far behind. Her “heart silenced by an ungraspable lament, still and snowy,” the young Raymonde April meditated on her destination: “Leaving to study, to work, to make a life, to settle in the big city, to love and suffer there, to start projects, to keep appointments, to pick up the pieces, to fly to other countries.”6 Since then, each time her photographs passed beyond the Pèlerins, the work has meant something different. The images also migrated to the big city, to settle there, do their work there, make a life for themselves, take a plane to other countries. They have been the raw material for so many stories that one has lost sight of where they came from. However, a thin thread hangs on, and it is still possible to make one’s way back to the source. If April regularly returns to Rivière-du-Loup, her work returns less often.When it does pass through, we take hold of it and embrace it.

1 Raymonde April found old photographs of these four views among her family souvenirs, and commented on them in Album XI of Aires de migrations (2005): “To the south: the house, the fields. To the west: the trains and St. François-Xavier Church. To the north: the River. To the east: the Collège and the park.”

2 Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, Volume One : Swann’s way, trans. C. Scott Moncrieff (New York : Henry Holt, 1922) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/7178/7178-h/7178-h-htm (accessed 22 May, 2013).

3 Françoise Sagan, With Fondest regards, trans. Christine Donougher (New York : Dutton, 1985) p. 139.

4 Raymonde April, “A Fly in Paradise”, in Thirteen Essays on Photography, Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, 1990, p. 206.

5 Raymonde April, Soleils couchants, Québec : Éditions J'ai VU, 2004, p. 54 (freely translated).

6 It was the artist who first spoke of “passing the Pèlerins.” (“dépasser les Pèlerins”). This passage, taken from her website, differs slightly from the published version: Raymonde April, “Raymonde April,” Du souvenir au devenir: Rivière-du-Loup 2000, Cap-Saint-Ignace: Plume d'oie, 2000, p. 393.

Translation: Darcy Dunton

Editing: Craig Rodmore